“I write books for teenagers because I vividly remember what it felt like to be a teen facing everyday and epic dangers. I don’t write to protect them. It’s far too late for that. I write to give them weapons—in the form of words and ideas—that will help them fight their monsters. I write in blood because I remember what it felt like to bleed.”

Sherman Alexie, author of The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian

I was just reading this New York Times article about book banning in Texas, and it amazes me that we still continue to have this debate over and over and over again. Sometimes it’s racism, sometimes it’s homophobia, sometimes it’s anti-intellectualism, sometimes it’s ignoring the separation of church and state, often it’s all of the above and more.

Even if you choose to ignore the root issues, one of the themes that seems to come up frequently in this article is parents expecting librarians to parent their children. At one point, book banning is likened to putting ratings on TV and movies, but I hardly see how this is the same. I have a friend who once got kicked from a screening of The Rocky Horror Picture Show for being unable to provide proof of their age, but that didn’t cause the showing to be canceled. It didn’t remove the movie from the multiple streaming services it’s on. And if my friend had been younger than 17, and had gone home and streamed it, the FBI wouldn’t have shown up at their door.

Movie ratings provide information about content that may not be appropriate for certain audiences. We, the audience, then decide how to handle those warnings. We have our freedom to choose what content we consume and, if we have kids, what content we provide to them. Just as the creators have the freedom (within reasonable limits) to produce their content:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

And yet we continue to see individuals pushing their own opinions, beliefs, or responsibility for controlling the media their children consume onto other people. Teachers and librarians have gotten in trouble, even lost their jobs, for offering access to materials that some find objectionable (not obscene, on an incitement to violence, simply objectionable).

To me, book banning seems to be employed as a grey, slippery area south of free speech but north of outright censorship. These individuals and organizations may argue that since they’re not stopping the books at the presses, they’re not restricting authors’ freedom of speech. However, they are restricting Americans’ access to the speech of others, which many would argue violates the First Amendment in principle, if not outright. Not to mention that many of these books are banned for reasons that are indicative of larger cultural issues, such as the oversexualization of queer identities, purposeful ignorance of historical racism, or attempts to enforce certain religious beliefs on others. The fact that these banned books spark so much controversial conversation is, for many, evidence of why they should not be restricted in the first place.

The fact that these banned books spark so much controversial conversation is, for many, evidence of why they should not be restricted in the first place.

Tweet

Luckily for those of us that love banned books, there is a long legal history leaning in our favor.

A Brief (Incomplete) Legal History of Book Banning

In the 1959 case of Smith v. California, the Supreme Court ruled that booksellers and other proprietors were protected by the first amendment from prosecution for selling “obscene” materials. The court unanimously agreed that a bookseller who had been jailed for 30 days for selling allegedly obscene material had had her First Amendment rights violated. They believed that enforcing such punishments would cause booksellers to further restrict public access to materials out of fear of arrest (which seems particularly relevant to the aforementioned NYT article, and the discussion of librarians being fired as a result of conflicts over book banning).

In 1976, the federal appeals court ruled in Minarcini v. Strongsville City School District (6th Circuit) that school officials could not remove books from libraries simply because they find them objectionable (although it was asserted that school board members have some discretion over textbooks). Excerpts from the verdict include:

“A library is a storehouse of knowledge. When created for a public school it is an important privilege created by the state for the benefit of the students in the school. That privilege is not subject to being withdrawn by succeeding school boards whose members might desire to ‘winnow’ the library for books the content of which occasioned their displeasure or disapproval….Neither the State of Ohio nor the Strongsville School Board was under any federal constitutional compulsion to provide a library for the Strongsville High School or to choose any particular books. Once having created such a privilege for the benefit of its students, however, neither body could place conditions on the use of the library which were related solely to the social or political tastes of school board members….Further, we do not think this burden is minimized by the availability of the disputed book in sources outside the school. Restraint on expression may not generally be justified by the fact that there may be other times, places, or circumstances available for such expression.“

Source

In the 1982 case of Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico, Supreme Court justice William J. Brennan Jr. stated that “local school boards have broad discretion in the management of school affairs,” but that this discretion “must be exercised in a manner that comports with the transcendent imperatives of the First Amendment,” and that banning materials based on “narrowly partisan or political” grounds would amount to an “official suppression of ideas.”

Courts have made other rulings relating to free speech in schools, such as when the California Supreme Court determined that offering religious materials in school libraries is permitted under the First Amendment, and when the United States Supreme Court affirmed that public school students retain their First Amendment rights while on school grounds.

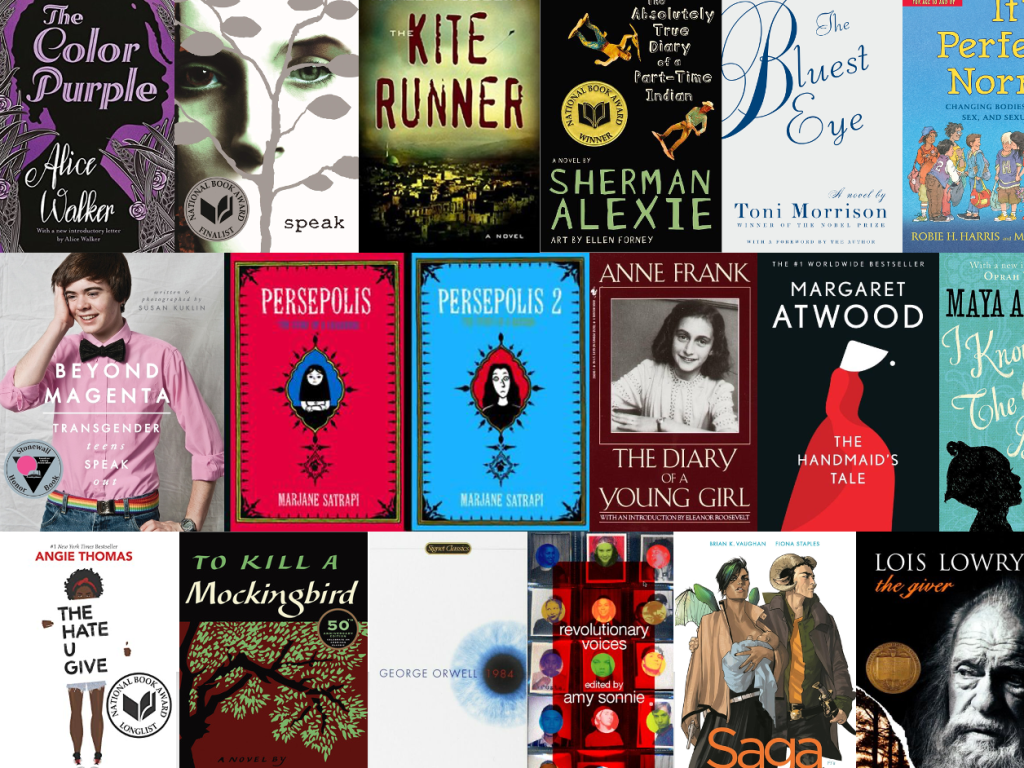

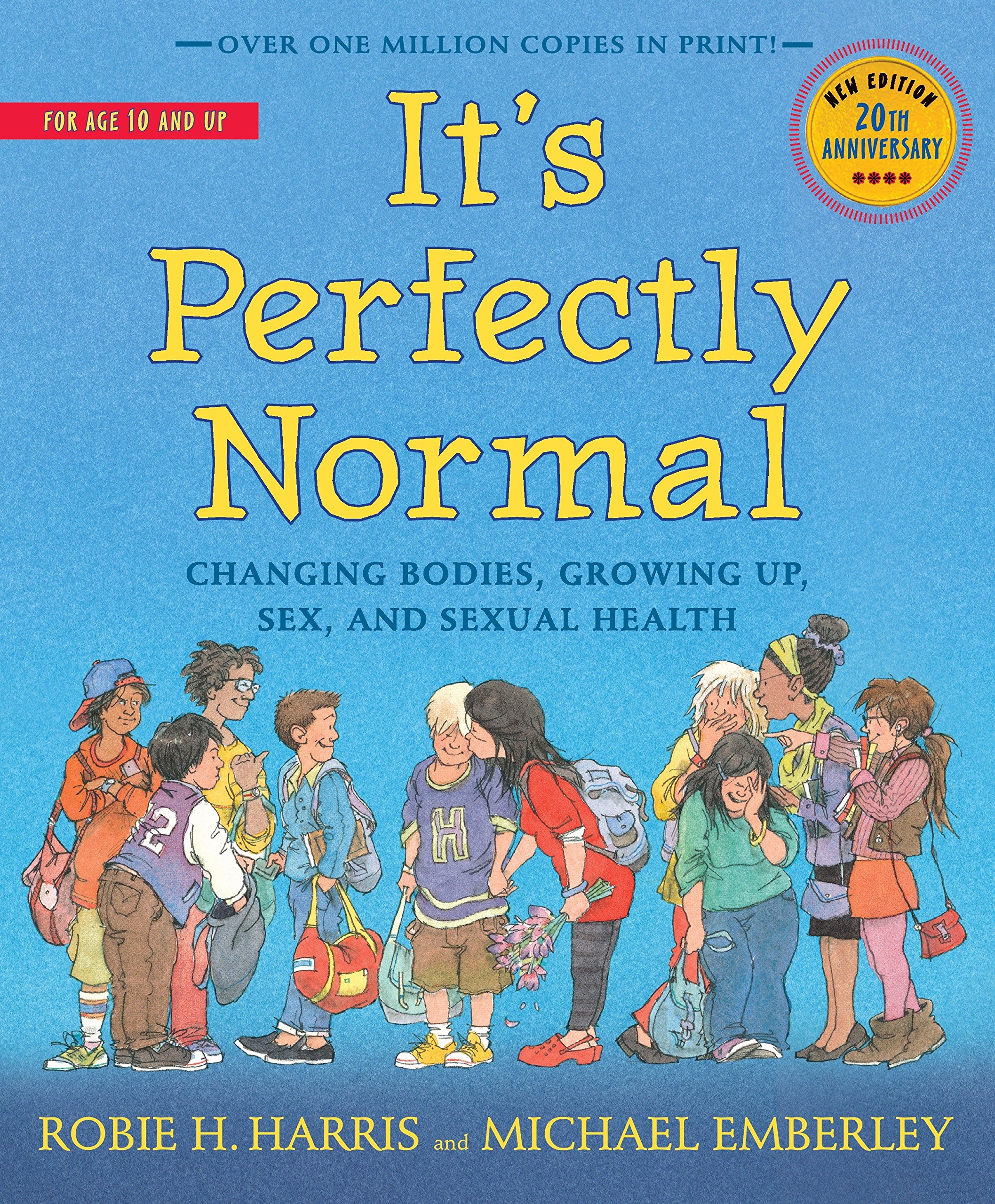

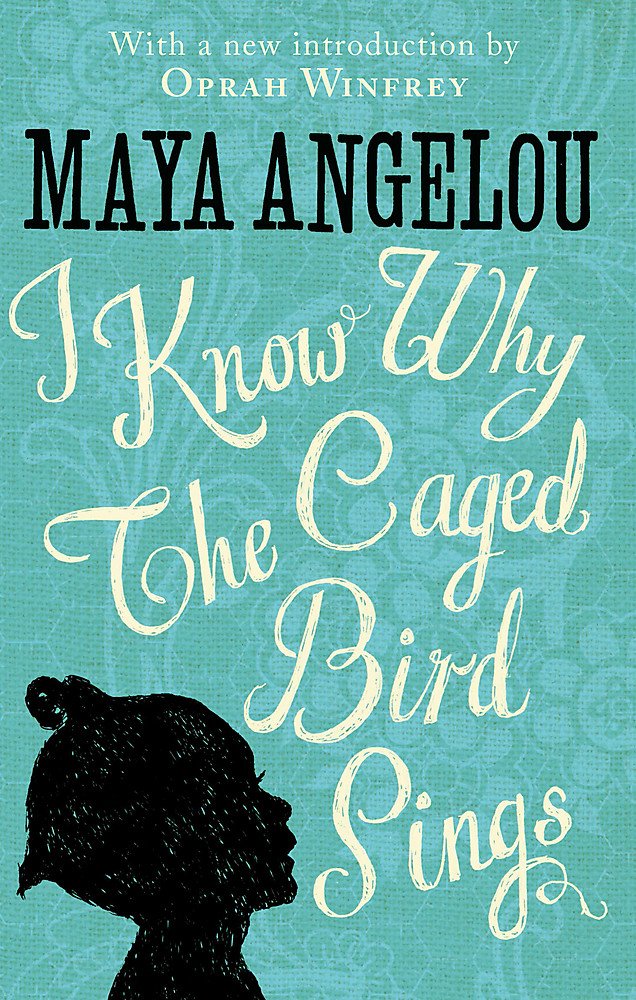

With the right to freedom of expression affirmed time and time again, particularly in regards to those who distribute books, it’s baffling to me that we continue to have this debate. With the American Library Association’s Banned Books Week coming up next week, I thought it would be relevant to share a partial, in-no-particular-order list of the most banned books of the last decade, and links to places to buy them. Simply for informational purposes, of course.

What’s your favorite banned book that you’ve read?

Leave a reply to Books Unbanned – Words Per Mile Cancel reply